Exploring EU Criminal law with the ECLAN Summer School 2023

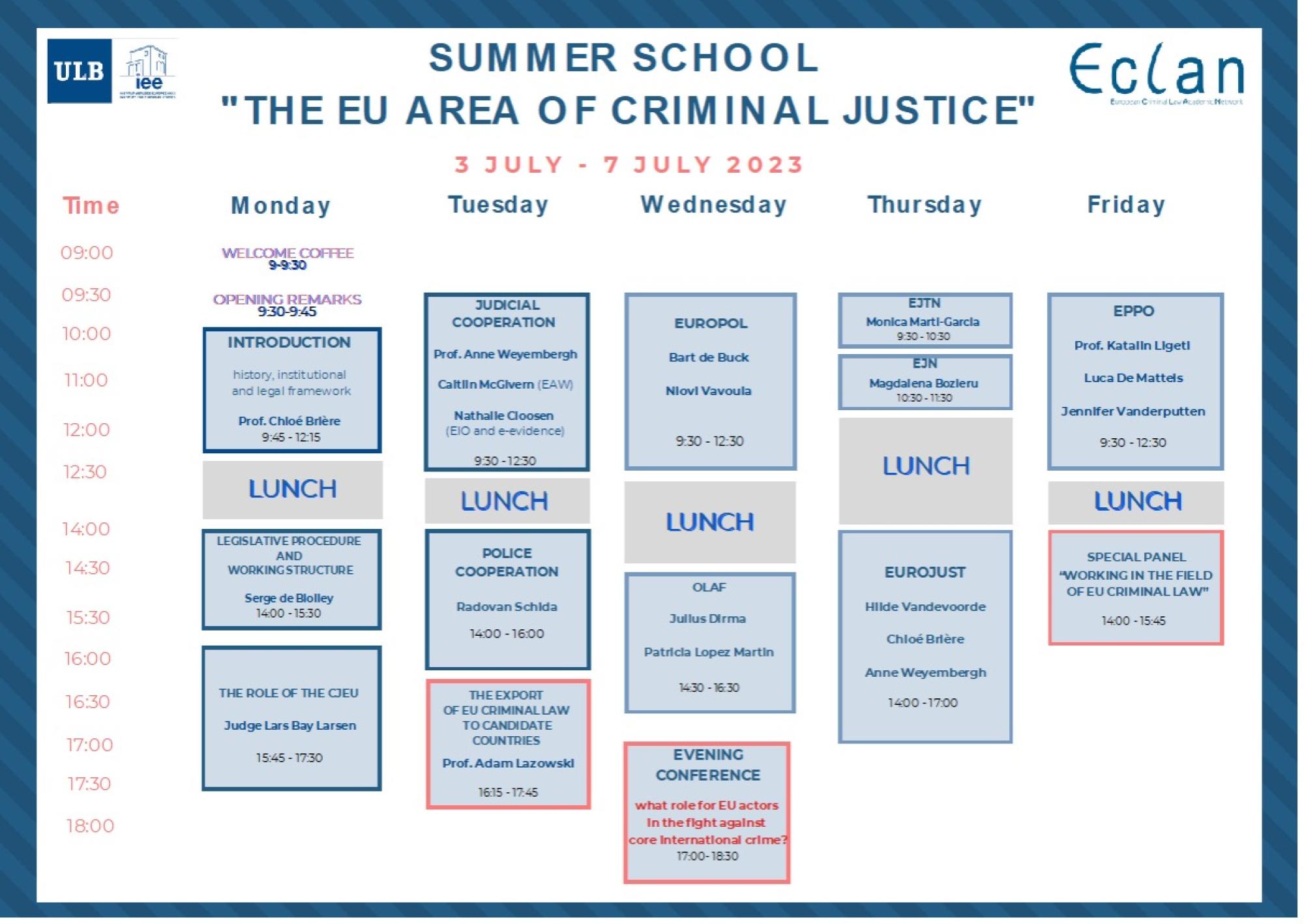

The ECLAN Summer School held from the 3rd to the 7th of July has been a great opportunity to focus on EU Criminal law with academics and practitioners.

During the first week of July (although it felt more like March due to the Belgian weather), the Institute for European Studies (IEE) welcomed criminal law scholars and practitioners for the unique ECLAN Summer School on the EU Area of Criminal Justice. The European Criminal Law Academic Network Summer School takes place every year in Brussels and this edition focused on the expanding role of EU actors in criminal law, offering diverse perspectives to provide a comprehensive understanding of the complexities within this evolving field. For five days, nearly 30 panelists and 40 participants gathered both in-person and online to explore European Criminal Law, which was a relatively hidden topic until the Treaty of Lisbon came into effect. While there has been increased activity in this field, it remains relatively niche. However, progress is being made, and the EU is endeavoring to promote it further, despite some skepticism from Member States. Currently, criminal law remains predominantly within national legislation, maintaining a territorial nature. This article takes the input from this extremely useful summer school, to explain EU Criminal law.

The history of EU criminal law

Prof. Chloe Briere, a GEM Alumna, delivered the introductory lecture, explaining the origins of the EU Area of Freedom, Security, and Justice. It was only with the Treaty of Amsterdam that EU Criminal law received a legal basis, even though discussions regarding the fight against trans-border crimes were already underway among EU Member States. The Schengen Agreement's signing in 1985 played a crucial role as it made the borders of national states more flexible, laying the groundwork for the development of criminal law.

During the late 80s and 90s, the EU initiated its laboratory for criminal matters, and its progress accelerated with the Lisbon Treaty. The removal of pillars dividing EU competences and the establishment of Title V of the TFEU provided for Cooperation in Criminal matters. Article 82 enshrined the principle of mutual recognition, obligating judicial authorities of Member States to recognize decisions made by other Member States. Article 83 granted the EU competences in criminal matters concerning trans-border crimes, such as terrorism, trafficking in human beings and sexual exploitation, illicit drug trafficking, illicit arms trafficking, money laundering, corruption, counterfeiting of means of payment, computer crime, and organized crime. This allowed for the adoption of Regulations and/or Directives under ordinary or special legislative procedures. Notably, there was also an emphasis on harmonizing legislation between EU Member States, as seen in the case of procedural rights.

The afternoon panels hosted distinguished figures like the Director of the Council of the EU, Serge de Biolley, the Director General in JURI 2, the Secretary-General of the Council, and the Vice President of the CJEU, Judge Lars Bay Larsen. They elaborated on the legislative procedure and the role of the Court of Justice in interpreting EU Criminal law. As legal scholars, understanding the role of the Council as the legislator in EU criminal law and the changed role of the EU Parliament was beneficial in recognizing the significant influence of national legal systems on criminal law. On the other hand, interacting with a judge handling EU criminal law cases allowed the participants to grasp the creative role of the CJEU and provided an impetus to delve deeper into the analysis of the CJEU's judgments.

Meeting the actors

The EU Member States cooperate with two EU Agencies, Europol and Eurojust, both established in 1999. Europol is the Agency responsible for coordinating Police cooperation. It deals with investigations, data protection, and other related areas. Initially, there was a Europol Convention, which required ratification. Eurojust, on the other hand, consists of national prosecutors, magistrates, or police officers of equivalent competence, detached from each Member State based on its legal system. Its main task is to facilitate the coordination of national prosecuting authorities and support criminal investigations, particularly those involving organized crime, often based on Europol's analysis. EUROJUST closely cooperates with the European Judicial Network, aiming to simplify the execution of letters rogatory.

Another essential entity in this cooperation landscape is the European Judicial Network (EJN), which acts as a network of contact points for facilitating cooperation and direct contacts between judicial authorities in the EU Member States. The EJN website offers e-tools required for the network's functioning and to facilitate cooperation among its members.

While these three actors are fundamental for improving cooperation, they are composed of judicial and police authorities responding to the will of their respective Member States, mainly dealing with trans-border crimes. For certain specific issues, the EU has instituted OLAF, The European Anti-Fraud Office, linked to the EU Commission. OLAF is not an independent organization. Established in 1988 and recently reformed in 2020, its mission is to investigate money laundering cases. It conducts administrative inquiries and prepares reports to be transmitted to the competent judicial authorities if necessary. OLAF's role has come under discussion due to its similarities with the European Public Prosecutor's Office (EPPO), created with the regulation of 2017/1371 and active since 2019. EPPO focuses on crimes against the EU budget, including money laundering and other practices that can affect the EU's economic stability. Unlike OLAF, EPPO is the result of reinforced cooperation, and not all Member States are part of it. EPPO functions as an independent judicial institution, bringing together one prosecutor from each Member State. Once it identifies the involved States and the territory of the principal crimes, EPPO contacts the delegated national prosecutor and provides the necessary materials to initiate trials in a Member State, which OLAF cannot do.

During discussions, panelists also covered innovative institutions used by the EU to improve cooperation, such as the European Arrest Warrant, the European Investigation Order, and Police Cooperation in general. Additionally, an excellent panel focused on the EU's role in promoting criminal law beyond its borders, a challenging but crucial topic.

Keep on studying the EU Criminal Law

The evening conference focused on the War in Ukraine and the EU's role in prosecuting international crimes, a pressing topic in the field of EU criminal law. The challenge lies in how to prosecute war crimes in Ukraine when neither the International Criminal Court nor Russia has jurisdiction in the country. Nevertheless, the conference highlighted how the EU has improved its integration in criminal law as a response to this conflict. Eurojust, for instance, established a group of coordinated prosecutors from Ukraine and EU Member States to conduct a joint inquiry into the war's events.

Overall, the conference provided valuable insights into the significant evolution of European Criminal Law over the years. The EU has emphasized the need for a harmonized approach to combat cross-border crime and safeguard fundamental rights within the European Union. The establishment of crucial instruments such as the European Arrest Warrant and the European Public Prosecutor's Office has facilitated cooperation among member states and streamlined judicial processes. Furthermore, directives and regulations have been implemented to address various criminal offenses, offering greater protection to victims, and ensuring fair treatment of suspects across borders.

In conclusion, European Criminal Law, once viewed skeptically as potentially infringing on the sovereignty of Member States, has become an essential area of knowledge for criminal law scholars. While there is room for further development, both the EU and institutions like universities and law firms should strive to deepen their understanding of this field. The summer school itself serves as an excellent starting point in this endeavor, providing a valuable platform for exploring and advancing knowledge of European Criminal Law.